May 2022

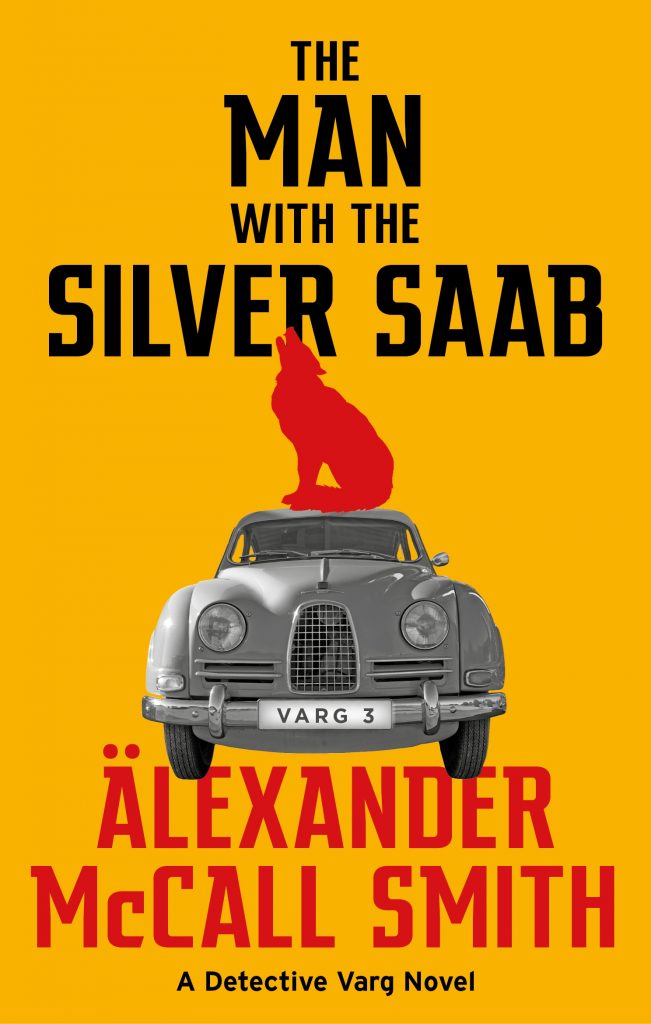

The Man with the Silver Saab is the third book in the Detective Varg series, it will be published in paperback in June. Below is an extract from the first chapter.

Chapter One: An Attack with Impunity

It happened very quickly. One moment, Ulf Varg’s hearing impaired dog, Martin, was enjoying his outing to the park, sniffing about in the bushes, pursuing ancient and tantalising smells, the next he was bleeding copiously from a number of severe head wounds. Above him in the trees, the unrepentant perpetrator of this outrage, a large male squirrel, bloodstained himself but clearly the victor, looked down on his victim with all the mocking impunity that the arboreal have for the land-bound.

Of course, these things often take place against a background of entirely ordinary events. A big thing happens while small things are going on all about it. Take suffering: Auden’s poem ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’, a reflection on Brueghel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, reminds us of just that – of how the Old Masters understood only too well the human context of suffering, about how it occurs when people in its vicinity are going about their ordinary business, their innocent routines. The tragedy of the boy falling into the sea unfolds while a ship sails blithely on, while a man ploughs a field unaware of what is happening in the bay.

Ordinary human business. So it was that when misfortune struck Martin on that Saturday morning, Ulf himself was chatting in the park to a fellow dog owner; a small boy was trying – unsuccessfully – to launch an un-cooperative kite, the boy being still too young to understand that kites require wind; and a young couple, newly in love, were having their first disagreement, on a park bench, about what to do that evening.

At first, Ulf barely noticed what was happening. His conversation with the other dog owner was about a puzzling series of incidents that had taken place in the park a few weeks earlier and that, in the opinion of the other man, had been scandalously under-investigated by the police. The incidents in question had occurred at night, and had all involved young women being approached by a man who, without warning, danced up and down in front of them shouting, ‘Cucumber! Cucumber!’ before rushing off into the trees.

‘It’s utterly bizarre,’ said Stig, Ulf’s friend in the park, about whom he knew very little other than that he was a doctor, and often overworked. ‘Seemingly, it was not all that serious, but the victims have all been young women in their late teens or early twenties and they’ve been pretty shocked by the experience. I know one of them – she works in the hospital pharmacy. A very open, friendly girl – and robust, too, I would have thought. But she was pretty shaken.’

Ulf tried not to grin. As a member of the Department of Sensitive Crimes in Malmö, he had seen just about every sort of bizarre behaviour that people were capable of, and he had long assumed nothing would surprise or shock him. Human perversity, he realised, was endlessly inventive. No sexual fixation or aberration, however ridiculous, struck Ulf as being unlikely or impossible: no private fantasy was too odd not to have its secret practitioners; nothing was out of bounds or unlikely as a vehicle or concupiscence. Eyebrows may have been raised in the past over these things, but not now, when all judgement as to personal erotic preference had been more or less abandoned in the name of . . . in the name of what? wondered Ulf. Freedom? Personal fulfilment? That must be it: our ability to disapprove had been blunted. And as disapproval waned, so too did morality itself change. It was no longer about goodness; it was about freedom to do what you wanted to do. In a world in which the concept of sin was so outdated as to seem like a medieval survival, the real offence seemed to be disrespect for the tastes and ambitions of others.

Ulf managed a serious face. ‘That’s not good,’ he said at last. ‘People should not frighten other people with . . . with cucumbers. That’s bad.’

There was a note of accusation in Stig’s tone. ‘Then why did your colleagues in the uniformed police not do anything? Why did they say: probably just a harmless crazy person? Why did they not lift a finger to investigate?’

Ulf felt he had to explain about operational discretion. ‘The police can’t do everything,’ he pointed out. ‘We have to pick and choose – according to what’s most urgent, or most serious. If somebody threatens to kill somebody, for instance, we drop everything to investigate.’

Stig nodded. ‘So you should.’

‘But if it’s something minor – a small theft, for example, or a row between neighbours – we might decide we just don’t have the time to look into it.’

‘All right – triage.’

Ulf thought the analogy apposite. ‘Yes, it’s what you people do in the emergency department, isn’t it? People come in and you decide who’s bleeding the most or who’s in most pain. It’s the same sort of decision.’

‘Yes,’ said Stig. ‘But . . . ’ He paused. ‘It’s just that people think the police have become soft. They think the police will let people get away with anything. And that’s particularly the case here in Malmö, where the police are anxious to not be seen to be picking on people.’ He paused, looking hesitantly at Ulf: one had to be careful what one said, and many people said nothing. ‘Is it because the police are party to our great Swedish pretence that crime doesn’t exist here? That people are imagining it? Or that it’s all socio-economic?’

Well, it is, thought Ulf. Or, at least, to an appreciable extent: crime was committed by those on the outside. But he looked away; he knew what the other man meant, but he knew, too, that he could quite quickly be drawn into the sort of conversation that he wanted to avoid. He reached for the anodynes. ‘We do our best,’ he said. ‘Sometimes, if you come down too hard on a particular group, it makes matters worse. They think you’re picking on them. And you might be – even subconsciously. You have to keep everybody onside – as far as possible.’

The doctor sighed. ‘I know, Ulf. I know. You’re right about that. We wouldn’t want Sweden to become an oppressive society.’

‘No, we wouldn’t.’ His agreement was real, and heartfelt; he would not have wanted to be a member of the Criminal Investigation Department of a heavy-handed government. Policemen could sometimes find themselves becoming oppressors because of the very nature of what they did, but Ulf had always seen the police as public guardians – the protectors, rather than the destroyers of people’s freedoms. That was his vision of police work in general, and in particular it was the philosophy that guided his approach to the unusual complaints with which his own department, the Department of Sensitive Crimes, was concerned

‘And yet,’ Stig continued, ‘a light touch should not allow people to go around frightening people by shouting “Cucumber” at them.’

He fixed Ulf with a challenging stare. ‘In the dark. In a park. Whether or not a cucumber is threatening is surely contextual, wouldn’t you say?’

It would be easy to laugh now, thought Ulf. Of course, cucumbers were capable of being threatening in a way in which peaches and nectarines, for instance, were not. But this man, this cucumberist, was really a minor irritant, in the way of those day release patients from the psychiatric hospital who go about the town carrying on one-sided conversations with their individual demons . . . or talking on their mobile phones – it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference between those who were talking to themselves and those who were merely having a telephone conversation through microphone headsets.

‘I’m sure they’ll do something,’ he said. ‘When they have the time, they’ll have a word with him.’

This was greeted with incredulity. ‘Have a word with him? Is that what policing has become? Having a word with people?’

‘It’s sometimes the most effective response,’ said Ulf.

‘But this is clearly sexual assault,’ Stig protested. ‘You don’t have a word with people who do that sort of thing.’

‘Does he have a cucumber with him when he jumps out in front of people?’ asked Ulf.

Stig shook his head. ‘I don’t know.’

‘Well then . . . ’

Stig was not sure whether Ulf understood. Sometimes policemen were a bit literal, he reminded himself. Did he have to spell it out? Surely not, and yet not everybody was sensitive to these things. ‘But the whole point, Ulf, is that the cucumber is phallic. It’s the most phallic of vegetables.’

Ulf felt a momentary irritation. He had read Freud, and felt that Stig’s remark verged on condescension. But his friend was probably right about the phallic nature of the cucumber: there was no other vegetable that matched it in that respect. And yet he reminded himself that people looked at things in their particular ways; cucumbers might mean different things to different people. That was not to say that they had no significance here: of course, symbolism was important in the investigation of crime, as the psychological profilers were at pains to point out. Those people found, in the criminal modus operandi, all sorts of clues as to motivation, and these clues often led directly to the perpetrator. There had been that man who had kidnapped domestic cats, always picking on Siamese, sometimes leaving them injured in their owners’ gardens or in the streets. The public had been revolted, as gratuitous cruelty to animals always met with disgust. The case caught the eye of the press, and this in turn brought in the Commissioner of Police, who said that every effort had to be made to find the culprit. A profiler was approached, and he they suggested that enquiries should focus on finding somebody who had been raised by a stepmother, and particularly by a stepmother

who kept Siamese cats. ‘He’ll be transferring his dislike of his stepmother – a very common problem – to the cats,’ he advised.

The police had paid heed to this diagnosis and had interviewed the entire membership of the local Exotic Cat Appreciation Club – fruitlessly, as it transpired. And then, quite by chance, Ulf had seen a magazine feature on a local pair of conjoined, or Siamese, twins. The author of the article had been sympathetic, but conveyed the impression that the twins were unhappy with their lot. Unhappiness, thought Ulf, does not always keep its head down: it may mould our response to the world. And at that point it occurred to him that the profiler had ignored the most obvious of all possibilities: attacks on Siamese cats might be (a) carried out by persons of a Thai background, or (b) by conjoined twins.

The twins, under investigation, proved blameless, and before Ulf had time to interrogate members of the local Thai community, the perpetrator of the attacks was filmed on CCTV chasing a Siamese cat down a street. He was apprehended and interviewed by the duty police psychiatrist, who reported that far from being motivated by animus against Siamese cats, he was, in fact, trying to steal them. This was to sell them across the border in Copenhagen, where unscrupulous dealers were prepared to take expensive pets without too many questions as to provenance. It was when the cats resisted that they were damaged, and that was entirely through ineptitude on the thief’s part.

It had become an open-and-shut case, but it gave rise to debate in Ulf’s department about how one might go about arresting a conjoined twin. Erik, his colleague in charge of filing and general support, had pointed out that if you took one such twin into custody, you would have to detain the other. And yet, the law would not countenance arresting somebody whom you knew, or even suspected, to be innocent. The courts would become involved and once that happened there would be only one outcome. In Erik’s opinion, the law was resolutely on the side of anybody who came to be detained by the police. ‘Once you’re arrested,’ he said, ‘you’re in a very strong position. A presumption arises that you’re being wrongfully held. It always happens like that.’

Anna, Ulf’s closest colleague, and one with whom he had for some time been secretly in love, was dubious. Erik was given to exaggeration, she thought, and was, by any standards, remarkably ill-informed on all subjects except fishing, on which his knowledge was extensive. What did Erik know about the doings of the Swedish criminal courts, bearing in mind that his only reading matter – as far as she could tell – was angling magazines such as Fish Today or Big Trout – copies of which were to be regularly spotted on his desk.

‘I don’t think you can say that, Erik,’ she said mildly. ‘Or not in so many words. The courts try to balance interests.’

‘That’s probably true,’ Ulf contributed. He was not entirely sure that this was the case, as he had seen many instances in which lawyers had managed to snatch manifestly guilty people from the jaws of justice. These people knew they were guilty as charged; their lawyers knew it too, as did the judges themselves, but the words of the penal code and the code of criminal procedure had somehow been interpreted in such a way as to allow wrongdoers to walk free. He had sometimes wondered how these notorious defence lawyers managed to sleep in their beds at night, knowing that their efforts had allowed anti-social elements of every stripe to be returned to society. Or did they not see it that way? Did they feel that it was better for the system to be weighted that way than to punish the occasional innocent defendant, the occasional victim of a police misjudgement? Nobody was perfect, and Ulf understood that this applied to police officers every bit as much as to others. At least his department, the Department of Sensitive Crimes, had, under his leadership, a reputation for being scrupulously fair to those whom they investigated. If he ever felt that they were investigating the wrong person, they would abandon the inquiry. That did not happen in some departments, where a far more cavalier approach was adopted and what seemed to count was that someone was apprehended, in order to keep the clear-up rate looking impressive.

Ulf thought there was a grain of truth in what Erik said, but he could not express this view in front of Anna, lest she think he agreed with Erik’s general opinions. It would not do at all if Anna suspected him of having anything in common with the world view of Fish Today, which occasionally published articles on subjects of a political or social nature. That, thought Ulf, was inexplicable: why should the editor of Fish Today stray outside his area of undoubted competence – fish – to opine on other matters? Was it journalistic frustration at being the editor of Fish Today then he might have wished to be the leader-writer on one of the national newspapers, or the editor of a respected political review? Plenty of people were in the wrong job altogether, or on a lowly rung of their chosen ladder; plenty of people were not where they wanted to be and might from time to time try to show what they saw as their true mettle.

Now, on the subject of conjoined twins, Ulf was unequivocal. ‘It’s quite right that the courts would order the release of the innocent twin. It would be completely wrong to imprison a person who had nothing to do with the offence in question.’

Erik thought about this for a few moments before replying, ‘Except for one thing, Ulf: how would you know that he – the other twin, that is – had nothing to do with the crime? How would you know that?’

Ulf shrugged. ‘We’re talking about a hypothetical case here, aren’t we? Let’s imagine that one of the twins has been seen doing something illegal. Let’s assume there are witnesses who say: That twin did it, the one on the left – or the right, as the case may be. Let’s assume we know beyond any shadow of doubt which one did it.’

Erik pointed out that this was not what he meant. What he meant was that the other twin – the one who had done nothing – might be guilty of abetting the offence because he’d failed to do anything to stop his twin from acting. ‘He becomes an accessory,’ he said. ‘By doing nothing to stop his twin brother, he becomes party to the offence. Simple.’

Anna thought ahead. ‘All right,’ she said, ‘but let’s think this out. Let’s say that we’ve gone beyond the issue of whether a suspect might be detained. Let’s say that we’re at the trial stage and the guilty twin has been duly convicted. The issue of accessory guilt has not arisen and there’s just one convicted person. What then? How do you punish the guilty twin without punishing the innocent sibling?’

‘You can’t,’ said Ulf. ‘You have to let him go free. He gets a warning, or something similar.’

This was too much for Erik. ‘But what if the crime is really serious? What if it’s homicide? What if the court thinks the offender is a danger to the public?’

This question was greeted with silence. At last, Ulf said, ‘In practice, this is not really an issue, is it? We don’t hear of Siamese twins being arrested, do we?’

‘Perhaps that’s because they don’t do anything illegal,’ suggested Anna. ‘If you’re a Siamese twin, you know there’s always going to be a witness to what you do – always – and so you watch your step.’

That had been the end of the discussion, and now Ulf thought that it did not really help him in his uncertainty as to how to deal with Stig’s complaint about police inaction over the outrages in the park. And he was about to say to Stig, ‘Let me ask my colleagues in the vice squad about this,’ when he heard a loud yelp from a clump of trees. Turning around sharply, he saw Martin engaged in a fight with what seemed to be an invisible enemy, struggling in a confusion of leaves and dust.

‘Your dog,’ shouted Stig. ‘There’s something going on.’

Ulf ran towards the trees. Martin had been off the lead and he had been vaguely aware of where he was, but had not been following him closely. Now he saw what had happened – what had been the consequences of his brief inattention.

When Ulf reached the scene of the tussle, the squirrel had already escaped and could be seen clinging to a branch of one of the trees, its tail an electric question mark of bristling fur. Ulf did not spend much time looking up at the branch, though – his attention was focused on Martin, who had been badly bitten about the head, and who was now whimpering at his feet.

A head wound in a human being can result in copious bleeding, and this also applied, it seemed, to dogs. Blood seemed to be pouring from the side of Martin’s muzzle and from his nose too, or from where his nose had once been. Ulf gasped in horror as he saw that the soft round bulb of the dog’s nose, to all intents and purposes like a small black truffle, had been almost severed. Instinctively he tried to press the nose back into place. It felt like a large crushed blackberry in his fingers and the attempted act of restoration brought a marrow-chilling howl of protest from Martin. For a few moments it seemed as though the dog would shake his nose off altogether, but the sinews still connecting the snout were tough, and the nose remained attached.

Stig had now joined Ulf, and his dog, Candy, tried to lick at Martin’s wounds, only to be discouraged by a further unearthly sound – something between a yelp and a howl.

‘You’ll need to get him to a vet quickly,’ said Stig. ‘He’s already lost a lot of blood.’

Ulf reached down to clip the leash back on to a collar now slippery with blood. He would have carried Martin back, although he was not a small dog, but he could not do so now as any approach to the injured animal was greeted with a baring of teeth and a savage growl. Yet once the leash was back on, Martin seemed keen to get back to the car, parked not far away, on the edge of the park.

‘You poor creature,’ muttered Ulf as he bundled Martin into the back of the Saab. He was indifferent to the specks of blood that immediately splattered the car’s cherished leather upholstery; all that counted now was to get Martin to Dr Håkansson as quickly as possible so that a painkiller of some sort might be administered. Ulf could not bear the thought of animal pain: pain and fear of death were things that we shared with the simplest of animal beings; we had more tricks than they did, but when it came to these basics, we shared that terrain with them, and were as vulnerable as they were.

He set off, and within a block or two encountered a traffic jam. A wedding celebration was taking place somewhere, a colourful ceremony from a distant culture, and the guests had parked inconsiderately. This had led to a build-up of normally free-moving traffic, and at points cars were reduced to walking speed. Ulf looked anxiously in his rear-view mirror at the injured dog. Although Martin’s instinct was to lick his wounds, the almost-detached nose and its tiny bond of tissue made this form of self-administered canine first aid impossible. Their eyes met in the mirror, the dog gazing imploringly at his omnipotent master, unable to understand why Ulf, source of all authority, a human sun, should be unable to bid this pain cease.

The silver Saab nosed its way through a cluster of cars, their drivers drumming fingers on their steering wheels, impatient or accepting, according to personal disposition. Ulf craned his neck to get a better view of what was happening ahead, where the long line of cars snaked out as far as a distant junction. It could be half an hour or even more before the tangle of vehicles sorted itself out, and by then it might be too late for Martin. The bleeding had not abated, as far as Ulf could tell, and there must be a point at which the dog’s heart would simply give out, as a pump does when it runs dry. How much blood did a dog’s body contain? Ulf knew that we had about five litres – a fact that he remembered from forensic medicine lectures at the police college – but he was not sure about dogs. A couple of litres, perhaps; certainly not much more, and Martin must by now have lost a good cupful or two. Then he remembered another curious detail, dredged from memory, not thought about for years. The lecturer in forensic medicine at police college, a desiccated-looking pathologist with a slight nervous tic, had remarked that while we made do with that five litres, an African elephant had roughly fifty times that volume. That was one of the few details that Ulf remembered of those ten lectures from Dr Åström, along with the pathologist’s explanation of death by shock – a cause of death he said he had encountered twice in his professional career, with one of the victims being a householder who had opened a cupboard door to find not one but two intruders hiding inside. The intruders had not raised a finger to the householder, but the shock of their presence was enough to cause his heart to fail. The other shock-induced death he had dealt with was that of a lottery winner who had died on realising that he had chosen the exact six figures that would bring him a jackpot of millions. He was a bachelor with no close family, and the millions, claimed on his behalf by his estate, had ended up in the hands of a charity dedicated to expanding public knowledge of coastal geology

His thoughts returned to Martin, and to the urgency of the situation, and at the same time his eye fell on the detachable blue lamp that he could put on the top of the car if an urgent summons came through. Powered from the power socket of his car, this light would flash intermittently, as might a lighthouse in the darkness. And it worked: seeing the blue light coming up behind them, drivers would slow down and pull in – exactly the course of action recommended in the Highway Code. This would allow Ulf to sail past unimpeded – something that was useful at some points in police work but that was not to be abused – as the Commissioner made clear in his circular on emergency procedures.

‘Police vehicles,’ he wrote to his section commanders, ‘are subject to the ordinary rules of the road, and I shall not countenance any abuse of the occasional – and I underline occasional – licence that we have to break these rules in the interest of a rapid response.’

Ulf hesitated. Was this an emergency of such a nature as to justify a blue light? It was certainly a matter of life and death, even if only canine life and death. And yet why should we distinguish between our lives and the lives of dogs? Dogs were meant to be our friends and felt so many of the things that we felt. Dogs had a sense of self. Dogs understood loyalty and friendship; dogs loved us, and would do anything for us, so why should we not do anything for them?

Ulf retrieved the light. Reaching out of his open window, he placed it on the roof of his car, where its powerful magnet sucked at the metal of the Saab’s bodywork. Ahead of him, a driver looked in his mirror and then obligingly pulled over to allow Ulf to pass. On the back seat, Martin bled onto the upholstery, whimpering, puzzled. He had forgotten what had caused his injury – dogs do not remember these things – but he knew that he was in pain and that the epicentre of this pain was his nose – or the place where his nose had once been.

The Man with the Silver Saab is available in paperback in from the 7th June